Part Two of Press and pressure: Ransomware gangs and the media.

In the first feature, we discussed the impact from ransomware gangs upon the media, how ransomware has altered various aspects of the threat landscape, including the significant recent trend of commoditisation and professionalisation. We previously took a look at the impact to the industry from ransomware actors giving these interviews and the extent that threat actors seem to relish the opportunity to give insights into the ransomware ‘scene’, with further discussion on the motivations.

Without further ado, let’s continue discussing Sophos Press & Pressure; Ransomware Gangs and the Media…

Press Releases and Statements

Some ransomware groups release what they term as “press releases,” a choice of terminology that carries its own significance. Take Karakurt, for instance, which dedicates a separate page to these releases. Among the three presently available, one serves as a public announcement for recruiting new members, while the others focus on specific attacks. According to Karakurt, negotiations soured in both latter cases, and these so-called ‘press releases’ are essentially veiled attacks aimed at pressuring the targeted organizations into payment and/or causing reputational harm.

Despite occasional errors or idiosyncratic phrasing, both pieces exhibit remarkably fluent English. One of them, mimicking the style of authentic press releases, even includes a direct quote from “the Karakurt team.”

Figure 1: Karakurt’s ‘Press Releases’ page

On the flip side, a press release from the Snatch group stands out for its lack of fluency and the absence of a specific victim focus. Instead, its purpose is to rectify errors made by journalists, a topic we will delve into shortly.

Figure 2: An excerpt from Snatch’s ‘press release’

This statement ends with the following sentence: “We are always open for cooperation and communication and if you have any questions we are ready to answer them here in our tg [Telegram] channel.”

A further example, this one from Royal (not formally titled as a press release, but with the heading “FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE”), announces that the group will not publish data from a specific victim (a school), but will instead delete it “in line with our stringent data privacy standards and as a demonstration of our unwavering commitment to ethical data management.” Here, the threat actor is arguably inviting a comparison between their own proactive action to ‘protect’ against the leak (for which they’re responsible) and the mishandling of ransomware incidents and sensitive data by some organisations – thereby aiming to portray itself as more responsible and professional than some of its victims.

Figure 3: A public statement by the Royal ransomware group

What’s particularly noteworthy here is the language; much of the style and tone of this announcement will be recognisable to anyone who’s dealt with press releases and public statements. For instance: “the bedrock principles upon which Royal Data Services operates”; “At Royal Data Services, we respect the sanctity of educational and healthcare services”; “Moving forward, we aim to…”.

It’s also worth noting that Royal seems to be trying to rebrand itself as a security service (“Our team of data security specialists will offer…a comprehensive security report, along with our best recommendations and mitigations…”). It has this in common with many other ransomware groups – who, in wholly unconvincing attempts to portray themselves as forces for good, have referred to themselves as a “penetration testing service” (Cl0p); “honest and simple pentesters” (8Base); or as conducting “a cybersecurity study” (ALPHV/BlackCat).

Rebranding is another PR tactic borrowed from legitimate industry, and it’s not unreasonable to speculate that ransomware groups may step up this tactic in the future – perhaps as a recruitment tool, or to try and alleviate negative coverage from the media and attention from law enforcement.

Branding

For ransomware groups aiming for media attention, branding holds immense significance. Captivating names and polished graphics play a crucial role in grabbing the attention of journalists and readers, especially on leak sites. These sites serve as the public face of threat actors and are regularly visited by journalists, researchers, and victims. Take Akira, for instance, with its retro aesthetics and interactive terminal. Such elements contribute to the overall allure and visibility of these malicious entities.

Figure 4: The Akira leak site

The LostTrust ransomware group (a possible rebrand of MetaEncryptor) is so patently aware that its leak site is its point of contact with the wider world, that it opted for a press conference graphic on its homepage.

Figure 5: LostTrust’s leak site. Note the blurb at the bottom, which includes the warning that “every incident is notified to all possible press in the region”

– echoing the warning from Dunghill Leak

On the other side of the coin, one ransomware group – either fed up with this trend, or getting per-formatively meta with it – decided to eschew a name and brand altogether.

Figure 6: A ransomware group which refuses to give itself a name – leading to it inevitably being named ‘NoName ransomware’

Highly refined branding isn’t limited to ransomware groups alone; it underscores a broader trend of increased professionalism across various categories of threat actors, as highlighted in our 2023 Annual Threat Report. This professionalisation extends beyond ransomware to encompass diverse threats. Notably, contemporary advertisements for malware products frequently feature compelling graphics and top-notch design.

One prominent criminal forum – which previously ran regular, well-established ‘research contests’ – even has its own ezine, including art, tutorials, and interviews with threat actors. An example, perhaps, of cybercriminals not only engaging with media outlets, but creating their own.

Recruitment

In March 2022, when a Ukrainian researcher exposed thousands of messages from within the Conti ransomware gang, many were taken aback by the level of organisation within the group. It exhibited a discernible hierarchy and structure reminiscent of a legitimate company, complete with bosses, sysadmins, developers, recruiters, HR, and Legal departments. The group adhered to regular salary payments, established working hours, and recognized holidays. Notably, it operated from physical premises. What’s particularly intriguing in the context of this article is Conti’s dedication to ransom negotiations and the creation of ‘blog posts’ for the leak site. Here, a ‘blog’ serves as a euphemism for a list of victims and their disclosed data. This highlights that activities such as responding to journalists, crafting press releases, and similar tasks may not be ad-hoc responsibilities for hackers in prominent, well-established groups. Instead, they could constitute dedicated, full-time roles, drawing parallels with the structure of teams in technology and security companies, like the example of Sophos X-Ops (if we’re not delving too deep into meta territory).

While many ransomware-related activities don’t require fluent English skills, this kind of work does – especially if threat actors are also going to be writing public statements. Such individuals have to be recruited from somewhere, and on criminal forums, adverts for English speakers and writers (and, occasionally, speakers of other languages) are fairly common. Many of these ads aren’t necessarily for ransomware groups, of course, but likely for social engineering/scamming/vishing campaigns.

While Sophos didn’t find any specific examples of threat actors attempting to recruit people with marketing/PR experience, this is something we’re going to keep an eye out for. Given the increasing ‘celebrification’ of ransomware groups (see LockBit’s tattoo stunt and similar developments) and the rebranding strategies discussed previously, it may only be a matter of time before criminals make more concerted efforts to manage their public images and deal with the increasing amounts of media attention they receive.

When things go wrong

Sophos observed that ransomware groups employ various strategies involving the media, such as referencing past coverage on their leak sites, engaging with journalists’ inquiries, participating in interviews, and employing the threat of publicity to compel victims to meet ransom demands. Nevertheless, experiences of public figures and companies demonstrate that interactions with the media are not consistently cordial. On multiple occasions, ransomware groups and other threat actors have taken issue with journalists, expressing dissatisfaction with what they perceive as inaccurate or unfair coverage.

The developers of WormGPT, for example – a derivation of ChatGPT, offered for sale on criminal marketplaces for use by threat actors – shut their project down, due to the amount of media scrutiny. In a forum post, they stated: “we are increasingly harmed by the media’s portrayal…Why do they attempt to tarnish our reputation in this manner?”

Contrastingly, ransomware groups often adopt a more assertive stance in their counterarguments. Take ALPHV/BlackCat, for example, which released an article on its leak site titled “Statement on MGM Resorts International: Setting the record straight.” This 1,300-word post criticised several media outlets for their failure to verify sources and disseminating inaccurate information

Figure 7: ALPHV/BlackCat criticises an outlet for ‘false reporting’

Figure 8: ALPHV/BlackCat criticises another outlet for ‘false reporting’, while admitting that it previously falsely reported a source of ‘false information’

The statement proceeds to target an individual journalist and a researcher, concluding with the assertion, “we have not spoken with any journalists…We did not and most likely won’t.” Interestingly, this instance illustrates a ransomware group abstaining from media engagement, instead endeavoring to shape the narrative by positioning itself as the exclusive and authoritative voice of truth. While there may be underlying power dynamics at play, delving into the psychology of ransomware actors is beyond our expertise and inclination.

Similarly, the Cl0p ransomware group attempted a comparable approach during a series of high-profile attacks earlier this year, exploiting a vulnerability in the MOVEit file-transfer system. In a post on its leak site, the group declared that “all media speaking about this are do [sic] what they always do. Provide little truth in a big lie.” Subsequently, the group specifically criticized the BBC for “creating propaganda” despite having previously emailed the BBC with information. Much like the ALPHV/BlackCat example mentioned earlier, Cl0p seeks to ‘set the record straight,’ rectifying what it perceives as inaccuracies in media coverage and presenting itself as the sole authoritative source of information. The overarching message to victims, researchers, and the general public is to distrust media reports and believe only in their version of the story.

Figure 9: The Cl0p ransomware gang calls out the BBC for ‘twisting’ information

An uneasy relationship

Cl0p isn’t alone in feeling mistrustful of journalists; it’s a common sentiment on criminal forums. Many threat actors – not just ransomware groups – dislike the press, and some non-ransomware criminals are skeptical of the relationship between journalists and ransomware gangs:

Figure 10: A threat actor criticises journalists for believing the “lies” of ransomware actors, and criticises ransomware actors “who are just trying to scam you [journalists] and chase influence.” Note that the sentiment here is not dissimilar to that expressed by ALPHV/BlackCat and Cl0p in the previous section

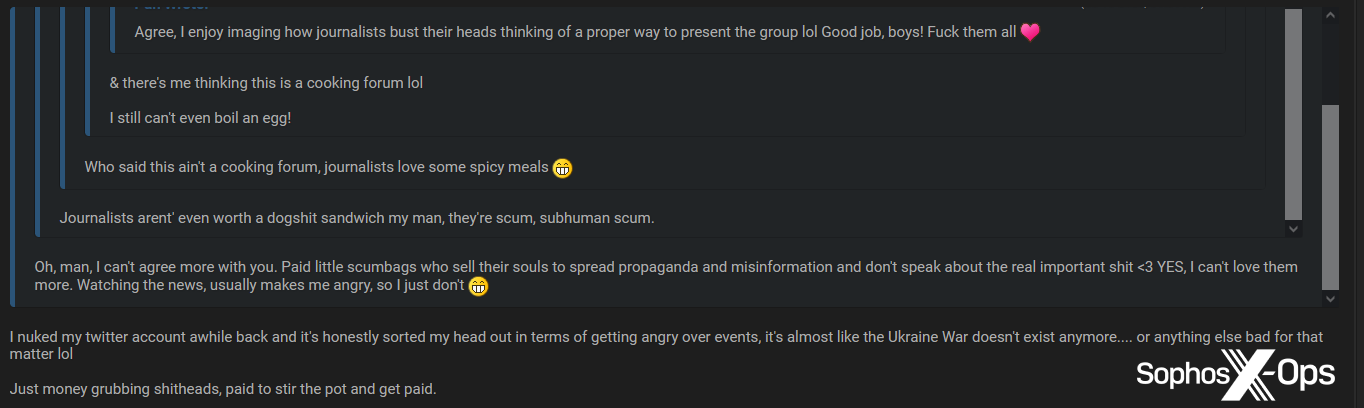

Just as ransomware groups are conscious that their leak sites are frequented by journalists, so members of criminal forums know that journalists have infiltrated their sites. High-traffic threads about prominent breaches and incidents will sometimes contain comments along the lines of ‘Here come the reporters,’ which occasionally descend into full-blown rants and insults.

Figure 11: Several members of a criminal forum insult journalists

Less frequently, threat actors may single out and/or target individual journalists, similar to the ALPHV/BlackCat instance mentioned earlier. While, as far as we know, these actions haven’t evolved into explicit threats, the intent behind such reactions is likely to create discomfort for the journalists involved and, in certain instances, to inflict reputational harm – a goal that is not always achieved successfully.

The carding marketplace known as Brian’s Club derives its name and branding from security journalist Brian Krebs. The site prominently features Krebs’ image, first name, and employs a play on his surname (‘Krabs,’ akin to ‘crabs’ for ‘Krebs’) on both its homepage and throughout the site.

Although this situation doesn’t appear to greatly bother Krebs (as he expressed being “surprised and delighted” by a response from the Brian’s Club admin after inquiring about the site’s compromise, with the admin humorously stating, “No. I’m the real Brian Krebs here 😊”), other journalists may not feel as comfortable in similar circumstances.

Certainly, researchers are not exempt from these tactics either and frequently face insults and threats on forums. The dynamic between threat actors and researchers is an intricate subject, beyond the scope of this article. However, one noteworthy example is worth mentioning. Following the release of the initial segment of a three-part series uncovering the inner workings of the LockBit gang, researcher Jon DiMaggio was taken aback to find that LockBit had changed its profile picture on a prominent criminal forum to a photo of himself.

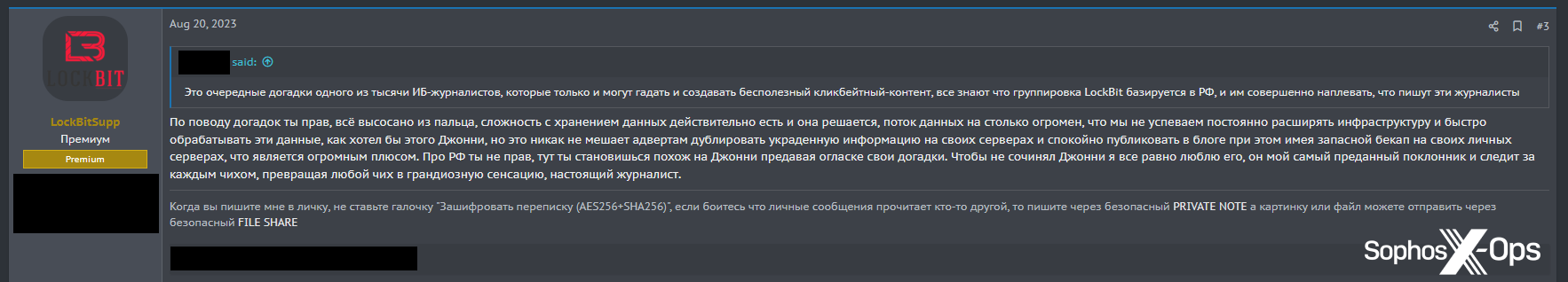

Following the release of the series’ concluding segment, threat actors engaged in discussions about the report among themselves. One participant displayed a dismissive attitude (translation: “These are just the latest guesses from one of the thousands of information security journalists who can only guess and create useless clickbait content”). In response, the LockBit account retorted, stating, “you are right, everything is made up…[but] no matter what Johnny says, I still love him, he is my most devoted fan and follows every sneeze, turning any sneeze into a huge sensation, a real journalist.”

Figure 12: LockBit posts in a discussion about DiMaggio’s reports

Therefore, even LockBit, a highly notable ransomware gang that has invested considerable time and effort into shaping its image, professionalizing its operations, and participating in media interviews, maintains a skeptical stance towards journalists and their motivations.

The paradox of certain ransomware groups actively seeking media coverage and engaging with journalists, despite harboring general mistrust and criticism towards the press, mirrors a contradiction familiar to numerous public figures. Similarly, many journalists acknowledge the dilemma of having reservations about the actions, ethics, and motivations of various public figures while understanding that reporting on those figures is in the public interest.

Acknowledgments

CSG have reshared this article from news.sophos.com. Sophos X-Ops would like to thank Colin Cowie of Sophos’ Managed Detection and Response (MDR) team for his contribution to this article.

Get in touch with us today to learn more about how CSG can help support you against Ransomware gangs.